| Indonesian language version |

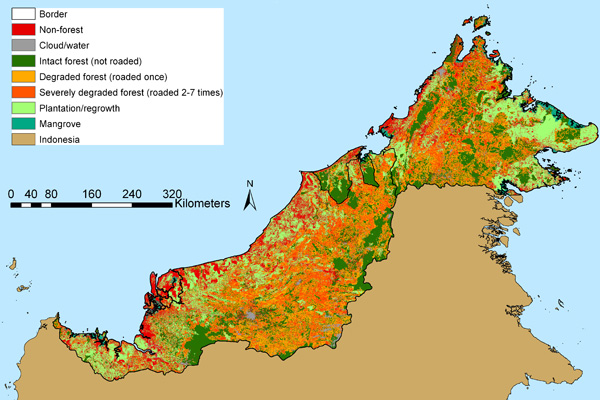

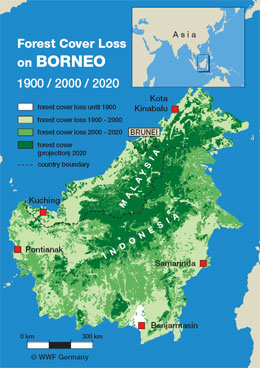

Major vegetation types of Borneo. Map modified from WWF's "Borneo: Treasure Island at Risk" report. The map is based on Langner A. and Siegert F.: Assessment of Rainforest Ecosystems in Borneo using MODIS satellite imagery. Remote Sensing Solutions GmbH & GeoBio Center of Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, in preparation, June 2005. Based on 57 single MODIS images dating from 11.2001 to 10.2002 with a spatial resolution of 250 m |

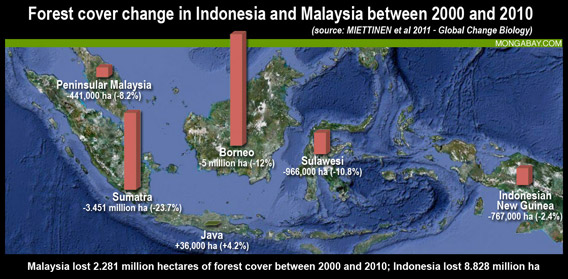

| 2000 | 2010 | Change 2000–2010 | |||||

| 1000 ha | % | 1000 ha | % | 1000 ha | % | %/yr | |

| Sabah, Sarawak, and Brunei | 11854 | 10015 | -1839 | -15.5 | -1.6 | ||

| Kalimantan | 29834 | 26673 | -3161 | -10.6 | -1.1 | ||

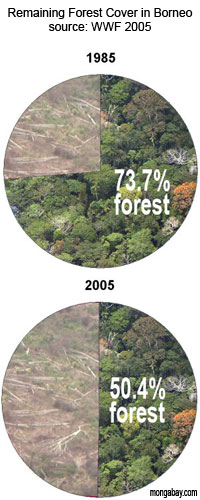

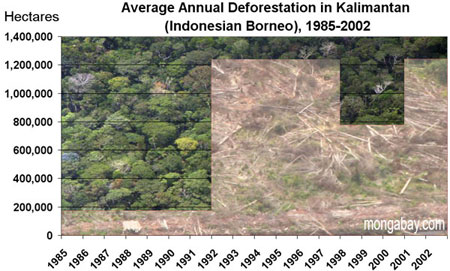

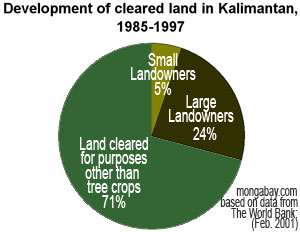

Results of Forest Conversion. Derived from figures found in WWF 2005 and based on data from The World Bank: Indonesia: Environment and Natural Resource Management in a Time of Transitio, February 2001 |

Young orangutan in Borneo. Photo by Rhett Butler |

| Area (ha) | Classification | What it means | ||

| 342,000 | Class I: Protection | Watershed and other "functional" forests. Cannot be logged | ||

| 2,685,000 | Class II: Commercial | Forests that can be exploited | ||

| 7,000 | Class III Domestic | Forests that can be logged for local consumption | ||

| 21,000 | Class IV: Amenity | Recreational forests, often degraded | ||

| 316,000 | Class V: Mangrove | Can be harvested | ||

| 90,000 | Class VI: Virgin Jungle | Conserved for scientific purposes | ||

| 133,000 | Class VII: Wildlife | Conserved as wildlife habitat |

| Classification | What it means | Area (M ha) | ||

| Conservation Forest | Protected | 4.6 | ||

| Protection Forest | Forests that serve environmental functions | 6.4 | ||

| Production Forest | Timber concessions | 14.2 | ||

| Limited Production Forest | Gazetted for low-intensity logging. Often located on steep slopes. | 10.6 | ||

| Conversion Forest | Designated for permanent clearance and conversion, usually for agricultural purposes | 5.1 |

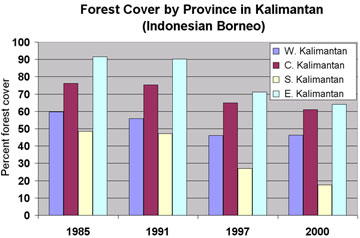

Forest cover in provinces of Kalimantan. (click to enlarge) |

Click to enlarge |